Reading “Poverty and Public Health,” a great article by colleague Mark Kelly in his Weld for Birmingham newspaper, was bittersweet for me.

It made me think of my friend Rev. Ronnie Williams. He should have been in it.

At the time Mark was interviewing and writing his story, Ronnie was battling the cancer that had spread from his lungs to his brain and other parts of his body. The cancer grew as the result of a severely addictive cigarette habit that gripped this public health advocate’s life for 45 years. Ronnie was 56 when he lost his battle and died on Sept. 23, the same day Mark’s article came out.

From the time that I met him two years ago, Ronnie began explaining to me the intricate connection between poverty and public health. Now, public health itself is a deep, multi-disciplinary field of preventative medicine. It requires a mind that can connect health with a broad spectrum of social factors, environmental conditions, political decisions and public policies — the “determinants of health.” It’s a lot to take in.

For years, Ronnie, a military veteran with a work background in IT, had immersed himself in this field, particularly as the former executive director for Congregations for Public Health. The community-based nonprofit came together under a grant to the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Public Health. He was also instrumental in bringing the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies‘ Place Matters initiative to Jefferson County.

In these capacities, he came to understand that the real root causes of health disparities among the poor, especially African Americans, was the nature of poverty itself.

Ronnie helped me understand that true poverty is not merely about people being too lazy to take care of their health, their schools, their communities. It’s about the persistent, negative systemic conditions that create the environment leading to poverty. It’s about people who are essentially locked in an “airtight cage of poverty,” isolated like islands in a sea of affluence, as Dr. Martin Luther King mentioned in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” It’s about people feeling hopeless and powerless to change the conditions that beset them, like polluting factories, industrial dumps and railroad systems that bring toxic materials into or through their neighborhoods.

Ronnie helped me understand that true poverty is not merely about people being too lazy to take care of their health, their schools, their communities. It’s about the persistent, negative systemic conditions that create the environment leading to poverty. It’s about people who are essentially locked in an “airtight cage of poverty,” isolated like islands in a sea of affluence, as Dr. Martin Luther King mentioned in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” It’s about people feeling hopeless and powerless to change the conditions that beset them, like polluting factories, industrial dumps and railroad systems that bring toxic materials into or through their neighborhoods.

These conditions breed a poverty of the mind that leads to poverty of the soul and spills out as the daily dysfunctions we see in Birmingham, in Bessemer and in most other spots where generations of poverty-stricken people live. Then, on top of that, these people are berated, belittled, marginalized, even shot dead as “thugs,” because they’re seen as threats and worthy of less sympathy than “normal” folk.

Some people have that something extra deep inside that allows them to escape the cage, to rise above their conditions. But they are generally the exceptions to the rule. Studies have shown that the majority of people born into poverty die in poverty. It’s for life. And it’s getting worse. As a group, African Americans have disproportionately lived well south of wealth/poverty line.

I noticed that Mark’s excellent article rarely included people who look like the people struggling in poverty. I’m not saying he didn’t look for them (he did ask me, by the way). Nor does their absence in the story imply that those folks aren’t out there, because they are (Ronnie was one).

The reason for this is that the organizations enabled to seriously address poverty were not initially developed by those living in the impacted communities. They are not directed by the indigenous people who are deeply, intimately and personally connected to the communities they serve.

Take the massive UAB system, for example. It was built over decades under the leadership of visionary people who saw the need to address poverty in our community and looked for ways to fill them. And they got lots of federal and private grants to help them. Lots of grants. Millions of dollars worth of grants essentially built UAB. It received monolithic amounts of money to throw at problems of poverty and related health disparities.

Yet the problems and the disparities persist. Why?

Because most of the entities tasked with fixing poverty aren’t attacking the root cause — economics.

For one thing, the millions of dollars they receive to study and fix poverty aren’t typically used to hire poor folk from poverty-stricken communities. Give the bulk of the money as salaries and wages to these folk, who’re well acquainted with the needs in their own community and have the best ideas on how to solve their problems. They can then circulate the money they earn back into their own community as they buy goods and services, pay church tithes and donate to smaller community nonprofits, often run by committed but unpaid stalwarts who are also working to end poverty a few folks at a time.

Some of the people who need to be hired — or even better, empowered with their own grants through their own organizations — are nascent leaders with workable empowerment plans who have arisen among the people most impacted by poverty. Train them and give them the resources they need to build capacity and to execute their poverty-eradicating plans within their own communities. These plans enable people to help themselves and their families escape the “airtight cage.” Their plans should include identifying and training a pipeline of future community leaders.

Execute the plans. Assess the plans. Modify the plans. Execute the modified plans. Repeat this process, often, until generational poverty is gone and general prosperity is the norm.

People making money can think better and focus on their future instead of their impoverished present. They go to school to get better trained. And with more earning potential, they can send their children to good schools where they learn a trade and/or prepare for college. And we know that impoverished children who get a good education usually get better jobs and get out of poverty.

Ultimately, poverty centers on attitudes about the distribution of wealth — who gets it, how they get it and when. Yes, anti-poverty programs have been co-opted or corrupted by self-serving individuals and institutions. But the shortcomings of a few shouldn’t cloud the work of many dedicated folk.

New leaders — like Kerri Pruitt of the Dannon Project, Jessica Norwood of Emerging ChangeMakers Network and Willie Barney of Empower Omaha — have formed their own organizations to do righteous work in the community in ways large and small. Older institutions with active branches like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Urban League and the Girls and Boys Clubs, among many other too numerous to name, have never stopped working for the good of the poor and the least of these.

But these individuals and organizations don’t typically receive the big grants. Nor are they typically the strategic partners of the mainstream organizations that do receive them.

Ronnie, one of these nascent community leaders, understood all this. And he knew what to do about it.

Unfortunately, Ronnie himself was “poor” in terms of material wealth. He was trying to build his own organization, The Public Health Network Inc. that would give him the platform he needed to address the problems and solutions he saw.

I was one of his board members, and we tried valiantly to make it work. He opened my eyes to the role of public health in my own efforts through Transformation Birmingham to identify and link new organizations rooted in communities of poverty to build capacity and to mutually support each other.

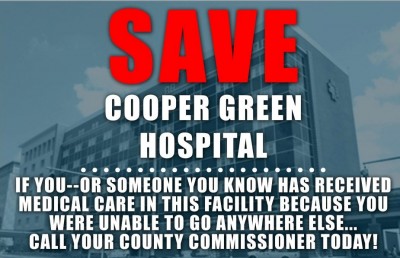

Despite the difficulties, Ronnie never stopped trying. He never stopped working in and for the community. He was never silent when it came to the needs of the poor and his people. He prodded me — a journalist who prefers working in the background — to speak up and out about the negative impact the closing of Cooper Green Mercy Hospital on the poor. He encouraged me to keep writing and telling the truth through Birmingham View, to keep building Transformation Birmingham, to keep the faith and continue the good fight.

Despite the difficulties, Ronnie never stopped trying. He never stopped working in and for the community. He was never silent when it came to the needs of the poor and his people. He prodded me — a journalist who prefers working in the background — to speak up and out about the negative impact the closing of Cooper Green Mercy Hospital on the poor. He encouraged me to keep writing and telling the truth through Birmingham View, to keep building Transformation Birmingham, to keep the faith and continue the good fight.

Out of the little he had, Ronnie gave of himself to the community he dearly loved, even as he faced the last stages of his life. The VA Hospital was his lifeline to the only healthcare he could afford. He was a soldier for the people until the very end.

I was in Montgomery on the Alabama Capitol steps with the NAACP and the Rev. William Barber II, leader of the Moral Monday Movement, when I learned that he’d been rushed to the hospital for the last time. I didn’t get the chance to see him before he died. I heard that he died with a smile on his face. I’m certain he was being told, “Well done, good and faithful servant! When you stood up for the least of these, you were standing up for ME. Welcome home.”

For those of us left behind, Ronnie, we will continue your work until it’s our turn to come home.