Dead men tell no tales and grand jury proceedings are secret — except in the case of the St. Louis County grand jury.

Prosecutor Robert McCulloch announced the foregone decision Monday night about the fatal confrontation between Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson and the young man he shot to death, Michael Brown, supposedly in self defense. (I learned about the grand jury’s decision on Twitter before McCulloch even opened his mouth.)

The media already had access to the reams of evidence that the grand jury considered. After spending several months listening to 70 hours of testimony and viewing volumes of other information, the panel of nine white and three black members came to the only logical conclusion based on the facts without judicial guidance or a real prosecutor: they could find no reason to indict Officer Wilson of any crime in shooting the 18-year-old Brown.

The carefully-orchestrated release of the information, even McCulloch’s unusual night-time press conference, was the way criminal justice powers that be in St. Louis chose to tell the world, “There’s nothing to the claims of a racially-motivated, extrajudicial killing here, people, so let’s move along.”

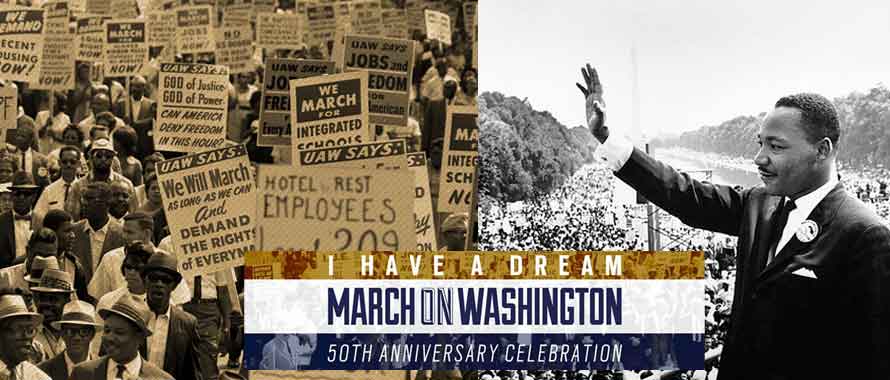

But people are not getting over it. Nor is life moving along as usual. The smoldering embers of charred police cars and buildings in Ferguson, the thousands of people across the country who flooded the streets over the grand jury’s no-bill are the exasperated outpouring of rage and grief over the handling of the Wilson-Brown case and, by extension, every other case involving police officers who’re killing unarmed black and brown civilians, seemingly without any accountability.