Martin Luther King, Jr. began writing his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” 50 years ago today. He wrote it as he sat in the city’s jail, arrested on Good Friday – April 12, 1963 – during one of the street protests and boycotts that his national Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth’s Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (an SCLC affiliate) organized to actively oppose racial segregation and its evils.

Locked in solitary confinement, the good reverend doctor had a lot of time on his hands. His aides brought him a newspaper, where he read an article by eight white clergymen of Christian and Jewish faiths. The Birmingham ministers criticized the Movement’s mayhem in the city, calling on King to stop the “untimely” protests.

The letter he wrote in response – scribbled around the edges of newspaper and on toilet tissue, then later transcribed by his aides into a formal document — is considered one of the most brilliant piece of protest literature. It powerfully and clearly demonstrates Dr. King’s intellectual discipline and moral authority on the issue of racial injustice. His famous “Letter” is read and studied around the world.

The first time I read “Letter,” I was about 33 years old, and sat wondering, “How in the hell did I get through high school and college (and I was an English major!) without being required to read this document!?” To me, it was as profound as a Pauline epistle. As an African American, it was soul-stirring in ways that are hard to put into a few words.

Now, a decade later, it is even more profound as I read it again, especially in the context of recent events.

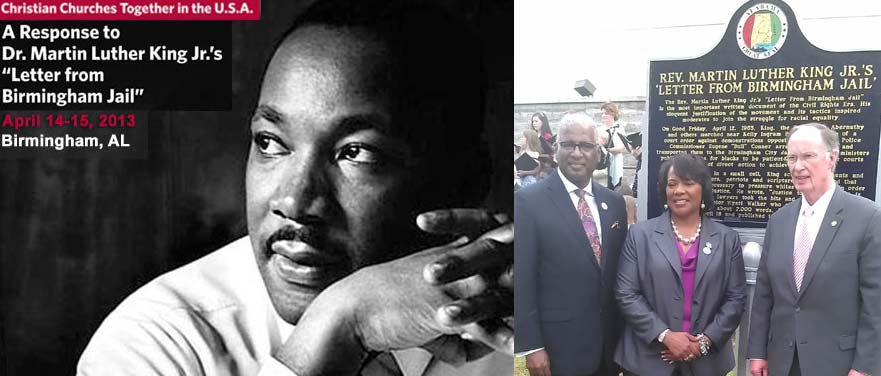

Sunday and Monday, Christian Churches Together U.S.A. held a meeting where its 36 constituent members crafted what amounted to a 21st century apology for failing to seriously address the concerns and just criticism that Dr. King laid out in his “Letter.”

At the end, each of the delegates signed their own response letter, confessing their denominations’ shortcomings by failing to speak out and act up as moral leaders should have done. As followers of Jesus Christ, King said, the church was supposed to be thermostats that changed the world, not thermometers that reflected the unjust status quo.

If Dr. King were alive today, he would no doubt see the same problems he wrote about continuing in a subtler, yet unabated form today.

During a Q&A session at Churches Together, a Catholic man asked his clerical leader what work was the church going to actively dismantle the underpinnings of structural racism, like disproportionately longer jail sentences for blacks than for whites charged with the same crimes, and other inequities that show up along the racial divide?

Another leader wondered aloud at the continuing embrace of white privilege that allows churches to avoid such issues all together because, well, they can. She said white privilege means people like her don’t even have to think about racial inequalities, much less do something to address them. And why would they want to, if it potentially means giving up the benefits that being white brings?

Dr. Virgil A. Wood, a 10-year co-working minister with Dr. King and the SCLC during the height of the Movement years, said it was easy to talk about “the Beloved Community,” where different people could live and work in the same place as Dr. King mentioned in his “I Have A Dream” speech, which also celebrates its golden anniversary this year.

“But when are we going to talk about the Beloved Economy” that addresses the glaring economic disparities among racial groups, he asked. Wood was working with Dr. King on that agenda at the time of his assassination. He said the poor shouldn’t have to wait another 50 years before the church gets back to that agenda.

But surprisingly, U.S. Congressman John Lewis – whose claim to civil rights fame was leading the voting rights march across Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965 – said that leaders like Wood who are pressing to continue King’s economic agenda needed to be “patient” and allow more time for that issue to be resolved.

Lewis sounded eerily like those clergymen King chided in his “Letter,” where he wrote, “Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be co-workers with God, and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation. We must use time creatively, in the knowledge that the time is always ripe to do right.”

Wood doesn’t have time to be patient. He’s 83 years old and wants to pass on his knowledge and passion for the Beloved Economy before he leaves this world.

Harry Belafonte, who came to Birmingham last week, is also a man on a mission. Like Wood, he played an integral role with Dr. King in the Movement, including Birmingham. Belafonte raised money and awareness with the Kennedy administration for jailed protestors, including King.

Though given honors at ceremonies last week, Belafonte was personally concerned about today’s youth. He said the older generation, by choosing to forget the shame of segregation in the selfish pursuit of personal wealth, dropped the baton. His generation failed to explain the stony, bloody road that he, Rev. Wood and their forefathers trod to get this current generation where it is today.

Rev. Bernice King, born just weeks before her father came to Birmingham in 1963, said that the current generation’s ignorance of the past struggles puts them at risk of failing to make progress of their own toward a better future.

And as the city unveiled a new marker at the site where her father was jailed, she challenged today’s churches to live up with the words and take an active lead to dismantle the remaining vestiges of racial discrimination.

Some have picked up the baton. Bryan Stevenson, president and founder of the Equal Justice Institute in Montgomery, spoke with the heart-wrenching eloquence of Dr. King Friday night about the people and situations he’s encountered in his work to fight poverty and racial discrimination in the American justice system. “The opposite of poverty is not wealth. The opposite of poverty is justice,” he said. Stevenson, 53, is proof that there are leaders in the post-Movement generation passionately committed to the continuing freedom struggle.

Despite having Barack Obama in the White House, despite having access to public venues, despite open doors of opportunity that the people before me did not have, the speakers at events this past week reminded me that we have still have work to do.

Yes, America is well on its way to the kind of society that Dr. King worked to advance, even when it meant suffering the indignity of being locked up like a criminal.

But it’s criminal when little black and brown children see themselves as bad, dumb and undesirable, as Dr. King wrote in his Letter 50 years ago. Even today, studies show that, if given a choice, some of these children would reject a doll that looks like them and ask parents to buy a white doll, which they perceive as smart, pretty and good.

My own friend told me she had to convince her little cocoa-brown daughter that she was beautiful and smart because of normal social incidents at her integrated school. Fortunately, my friend had teachers in the family that helped the child overcome her reading problems; she now reads above grade level. If children, the bellwether of our society, can internalize these racial thoughts that can impact their lives at such young ages, then certainly racism is real and still here.

If we are serious about finishing Dr. King’s unfinished work, then we all need to re-read his “Letter,” as some have done around the world today and tonight at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. After 50 years, I think it’s time to roll up our sleeves and resolve the remaining deficiencies Dr. King outlined in his “Letter,” under the power of the same Spirit that guided him.