The more I learn about the Civil Rights Movement here in Birmingham, the more I stand in awe. It took sheer nerve and raw power for those who put themselves in harm’s way to relentlessly pursue the true spirit of the American ideals, even when those ideals did not apply to them.

They truly believed in the Declaration of Independence’s towering words, “We,” meaning the founders of what would become the United States of America, “hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Of course they knew that the Founding Fathers’ did not necessarily intend to extend these rights to millions of African slaves or their descendants.

It didn’t matter. The power of those words and the desire for a better life fueled a movement of Black folk in Birmingham to do something that today seems simple, but back then was very bold – and dangerous. They crossed the color line of Center Street and moved into a whites-only zoned neighborhood in Birmingham’s Smithfield Community.

And when they ran into legal (well, technically illegal) roadblocks, they called on the man they knew could help them: Arthur Davis Shores, who for a decade from 1940 was the only practicing black attorney in the entire state of Alabama.

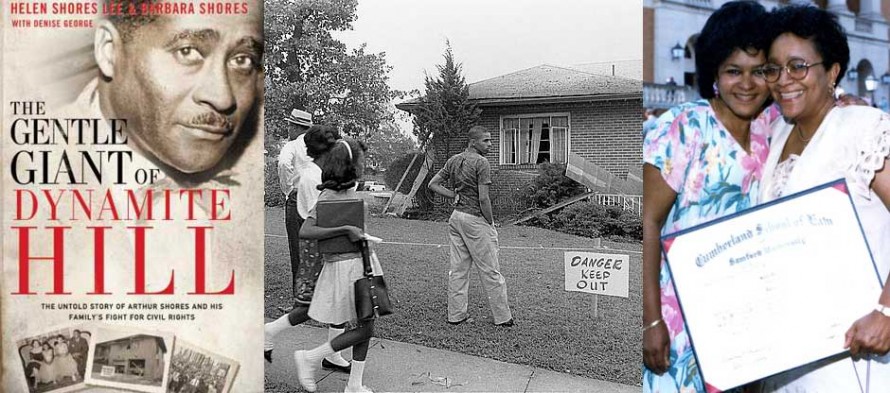

For daring to cross the color line, for daring to exercise their right to the pursuit of happiness of better housing, Ku Klux Klan terrorists threatened these black families and bombed their homes. The bombings became so regular that the gentle slope rising along Center Street, just northeast of Legion Field, was dubbed “Dynamite Hill.”

And for daring to file lawsuits in the 1950s challenging racial zoning laws that had long been declared unconstitutional (in 1917!), Attorney Shores became a villain, public enemy No. 1 of segregated Birmingham’s law and order, until the fiery and in-your-face preacher Fred Shuttlesworth took that title. Yet Shores continued his dogged pursuit of the American ideal for people of African descent, despite the real dangers and risks to himself and his family.

His daughters, Helen Shores Lee and Barbara Shores, said they asked their father why he put up with the threats of violence and the blatant disrespect by lawyers and judges in Southern courtrooms where he waged legal battles against legal segregation, why he ignored the pleas of his wife to move away to another city. His answer, they said, was simple.

“I’ve been called to help my people.”

That’s what they remember about a man short of stature, but possessing a giant heart. He gave himself unconditionally to a God whom he believed would protect him and his family, and to his people who deserved the same treatment under the law and the right to enjoy those American ideals as any other citizen.

The sisters have poignantly told their father’s story from their ring-side view of history in their book, The Gentle Giant of Dynamite Hill, co-authored with Denise George.

The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute is hosting the Shores sisters’ book signing today from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m.

Talking with them about their father and Birmingham’s past is a powerful history lesson that makes me appreciate so much more the freedoms that I take for granted as mine. The price of freedom for me was an unsettling childhood for them.

Barbara says she was almost the victim of a kidnapping from school. Hot-headed Helen said her father saved her from a long jail sentence when he pushed her hand just as she fired a .45 pistol at a car full of white youths who screamed ugly epithets and threats as they rolled past the house. In the days when their father fought to get Artherine Lucy enrolled as the first black at the University of Alabama, armed neighbors surrounded their house to keep the family safe.

And they were not safe. Terrorists often shot into the Shores’ home and, thankfully, the bullets missed as the family scrambled to the floor. The large plate-glass window was shot out so much that their father replaced it with a multi-pane window that was easier to fix. Two bombs detonated at their home in 1963. One blast killed Barbara’s beloved cocker spaniel. Another injured Mrs. Shores, Theodora. Another bomb that failed to detonate in March 1963 would have done grave damage.

But the Shores sisters also remember plenty of love from doting parents, instructions on how to pray for their enemies and lots of fun. Heck, they even rode like little cowgirls on the back of future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, who stayed at their house when he came to town to work on court cases with their father. In fact, both men – ace civil rights lawyers of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) – worked on the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education Topeka Kansas. Their historic win in 1954 struck down “separate but equal” doctrine and effectively closed the door on the South’s noxious segregation laws.

To hear their story is to enter a world I can’t remember or recognize, because I wasn’t born and the life I lived was completely integrated.

Many today, both blacks and whites, say this past is the past and it needs to stay there. It brings up painful memories that are best left alone. It’s best just to move ahead and forget ancient history.

That sounds wise, except for the rhetoric I’m hearing in “post-racial” America that sound eerily similar to some of the things said all those years ago – states’ rights, law and order, voter ID laws, blatant disrespect for ethnic groups, steering qualified minority homeowners to subprime mortgages and other things that seem out of place in a world where we have supposedly overcome.

These things suggest to me that history’s lessons aren’t being passed along to the new generation, that we’re falling back in some ways, that we’ve forgotten how we got to where we are.

Remembering can be painful, but forgetting can be dangerous.

Thankfully, Helen and Barbara Shores are here to remind us of their father’s legacy, making sure the next generation does not forget the price that was paid so that America’s founding ideals now apply equally to us all.

[…] following the program the NAACP will host a book signing “The Gentle Giant of Dynamite Hill” the life and times of Attorney Arthur Shores by his daughters: Judge Helen Shore Lee and Barbara […]